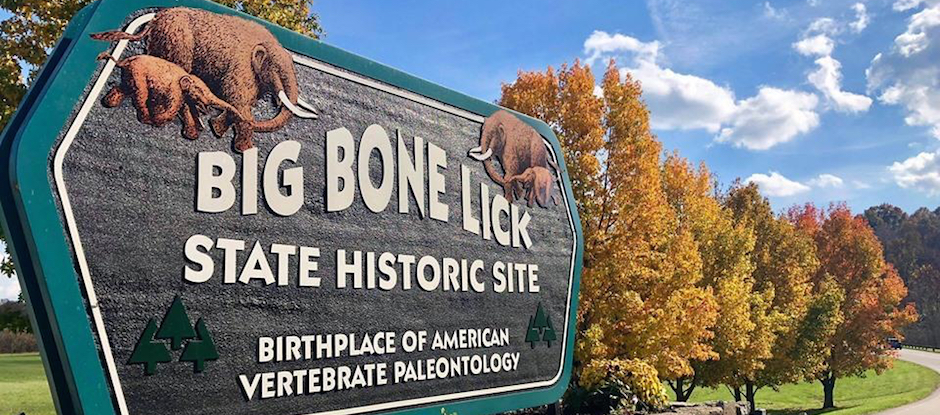

Visitors to Big Bone Lick State Historic Site find nature and a trove of incredible ancient history native to Boone County

by Juli Hale

Long before Boone County was incorporated, the area now known as Big Bone Lick State Historic Site was already on the map and attracting major attention.

Maps from as early as the 1740s marked the area as the site of the discovery of never-before-seen massive animal bones. The topographical claim drew explorers, scientists and collectors, including Meriwether Lewis and William Clark (yes, that Lewis and Clark), who visited the area separately to collect specimens at the behest of President Thomas Jefferson. The Pleistocene megafauna fossils found there gave the park its name; the revelation that the remains belonged to extinct animals brought about the first-ever paleontological dig, earning the area its claim as the birthplace of vertebrate paleontology.

Today, the park’s approximately 500,000 annual guests are just as likely to visit for its camping and hiking facilities as for its historical aspects. Its 62 campsites and 4.5 miles of hiking trails mark it as a go-to destination for those wanting to spend a weekend or a day enjoying nature.

Claire Kolkmeyer spent many weekends during her childhood camping at the park and exploring its trails. As a child, she met the park’s staff and learned the park’s history from them. She developed an avid curiosity about the land and its previous inhabitants and a “a slight obsession” with Lewis and Clark. Today, as the park interpreter/program director, she strives to build the same type of emotional connection between the park and its visitors.

“We really want to push the park back to its glory days,” Kolkmeyer says, adding that there are plans to reintroduce some fan-favorite events from years past, including an Easter egg hunt, Christmas in July and Halloween weekends. “Christmas in July used to be one of the biggest things in the park. There were tree cookie ornaments and a Christmas bike parade. I want people who haven’t visited in a while to come back and see the park and see that we are on the rise.”

Even for those just looking for a little time away from their day to day, it’s easy to run into a history lesson with so much scattered throughout the park. The Discovery Trail—an easy trail for all ages and fitness levels—starts at the Magafauna diorama, a life-size display of a woolly mammoth, mastodon, ground sloth, bison and scavengers feeding on carcasses in a salt bog, and winds along Big Bone Creek past interpretive panels that detail the history of the area during the last Ice Age. The diorama is scheduled for upgrades this summer, including new signage and, possibly, some new additions to the collection.

Kolkmeyer says plans include the addition of Paleoamerican (referring to the first peoples to migrate into North America during the late Pleistocene period) figures to better present the full story of why so many partial skeletons have been found in the area. Though the theory was once that these large mammals got stuck in the mud there and died, the more commonly accepted theory now is that the plant-eating animals—which came to the area for the widely available salt licks—were tracked there by the Paleoamericans who hunted and butchered them on site. This explains the lack of full skeletal remains.

“I love the trails, museum, bison and heritage information placed to read along the trails and in the museum. This heritage is very important to read about and see at Big Bone Lick,” says Lisa Murphy, who visits often throughout the spring and summer. “I love learning and seeing documentaries about it at the museum. The skeletal (remains) they recovered here are amazing and well preserved.”

The Bison Trace Trail, another easy trail, guides hikers along a lightly wooded path that ends at the gated field that is home to the park’s bison herd. Viewable every day of the year, the dozen bison that call the park home are representative of the wild herds that once roamed the area and were hunted to the brink of extinction. The bison recall the park’s prehistoric past and are the only living mammalian link to the Ice Age. According to Kolkmeyer, the bison are the biggest attraction in the park.

At the park’s Visitor Center, guests can get a different kind of view of the other animals that used to live on the property. A replica of an 8-foot Harlan’s ground sloth skeleton greets visitors. Standing on its back legs with its claws outstretched, the 2,000-pound sloth is an imposing figure that provides perspective on the great size of the animals that once roamed the area. A leg bone from an actual ground sloth, which was found on the property in 2017, is also on display. A massive mastodon’s skull and tusks sit nearby, mixed among the murals and display cases filled with other finds found on park property over hundreds of years.

According to Kolkmeyer, it isn’t uncommon to hear visitors call the sloth skeleton a dinosaur, but she insists these historical remains are much cooler than dinosaurs.

“Megafauna are separated by millions of years from the dinosaurs,” she says, “but these animals came out of this valley and some of them were first discovered here. I’ve always thought that was really cool.”

It is a feeling that she shares with her visitors, especially the youngest ones who come to the park. School classes, youth groups and Scout troops are regular visitors to the park where they can take a tour, view the displays and participate in hands-on programs designed to engage the students and build excitement for the history of the area.

Pat Fox, a former teacher and the current president of Friends of Big Bone, a nonprofit volunteer group that is dedicated to improving the resources at the historic site, is equally passionate about the park and stressing its significance to a new generation.

“You have to go past the beauty of the park and the enjoyment of the natural area itself,” she says. “There is just so much here that is left unsaid. I love history and I’m amazed that there is so much connected to this park.”